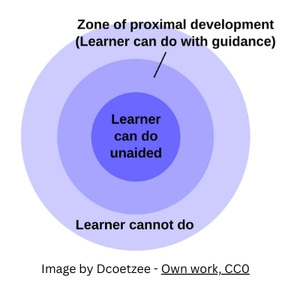

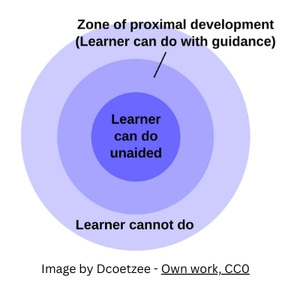

Identify the Learner’s Zone of Proximal Development

The zone of proximal development, proposed by the renowned psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1962), refers to the difference between what a person can achieve independently and what they can achieve with support (e.g., through effective modeling or scaffolding). More specifically, the term proximal indicates that the individual is close to mastering the skill independently. Understanding a learner’s zone of proximal development recognizes that learning something new is usually possible with appropriate support.

Presume the Ability to Learn or Expand Upon Symbolic Communication

Symbolic communication allows communication to convey a message without additional interpretation from communication partners. It’s a crucial way to support an individual’s overall quality of life.

At a simple level, using a graphic symbol to represent a preferred object to replace physically bringing a communication partner to a desired object can lead to significant gains in symbolic communication over time. But intervention should always be directed toward a higher level of symbolic communication, assuming that doing so will ultimately provide the learner with the means to convey more complex ideas and thoughts. If a learner demonstrates an understanding of one symbolic level, presume they are capable of transitioning to the next, more abstract level with the help of targeted instruction.

Always Incorporate Language Arts Instruction

Although it may be necessary to first focus on helping students communicate basic needs and wants, it’s also important to include language arts instruction. It’s estimated that up to 90% of learners who use AAC enter adulthood without the functional literacy skills to participate in meaningful work or life activities (Foley & Wolter, 2010).

Language arts instruction involves developing language skills that can improve students’ symbolic knowledge and advance grammatical understanding and use. Literacy instruction must begin with presuming potential, because if potential is not presumed and literacy skills are not taught, they will not readily develop. Learning to read is a developmental progression that incorporates knowledge and skills in a variety of domains, including:

- Emergent literacy skills

- Language skills

- Phonological awareness

- Letter-sound correspondence

- Decoding skills

- Comprehension

As part of AAC system training, many non- or minimally speaking learners are introduced to graphic symbols systems focused on expressive and receptive communication. We firmly believe that the symbolic knowledge that drives the AAC system can also form the basis of a reading program—albeit more symbol-based than text-based.

Many learners who are non- or minimally speaking may not become proficient text-based readers. However, their recognition and use of symbols can be used to support a reading approach that allows them to compose and read words, phrases, and sentences—in this approach, graphic symbols will form the foundation for what is produced or interpreted. In other words, students may experience considerable difficulty with traditional reading, but they’re often successful at identifying (and naming) the graphic symbols within their AAC system or other visual supports.

***

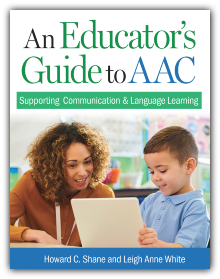

Go deeper with the book behind this article! Get practical guidance on nurturing language and communication skills—and improving quality of life—for students with significant communication needs.

COMING SPRING 2026!

An Educator’s Guide to AAC

Supporting Communication and Language Learning

By Howard C. Shane, Ph.D., & Leigh Anne White, M.Ed., M.S., CCC-SLP

By Howard C. Shane, Ph.D., & Leigh Anne White, M.Ed., M.S., CCC-SLP

Created by AAC pioneer Howard Shane and speech-language pathologist Leigh Anne White, this is the educator’s definitive guide to understanding AAC and improving outcomes for K-12 students who are non- or minimally speaking. Learn best practices for leveraging AAC to boost students’ expressive and receptive communication and language learning competence, with care and respect for each learner’s individual strengths and differences.

*This article is adapted from the upcoming book An Educator’s Guide to AAC by Howard Shane and Leigh Anne White (available in April 2026).

*This article is adapted from the upcoming book An Educator’s Guide to AAC by Howard Shane and Leigh Anne White (available in April 2026).  Incorporate Dynamic Assessment to Develop Attainable Goals

Incorporate Dynamic Assessment to Develop Attainable Goals

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post a Comment