For anyone who works with people with disabilities—or is getting ready to launch their career—learning the history of our attitudes and actions regarding disability is essential. To appreciate how far we’ve come and envision an even brighter and more inclusive future, it’s important to confront the past with an honest, unflinching eye.

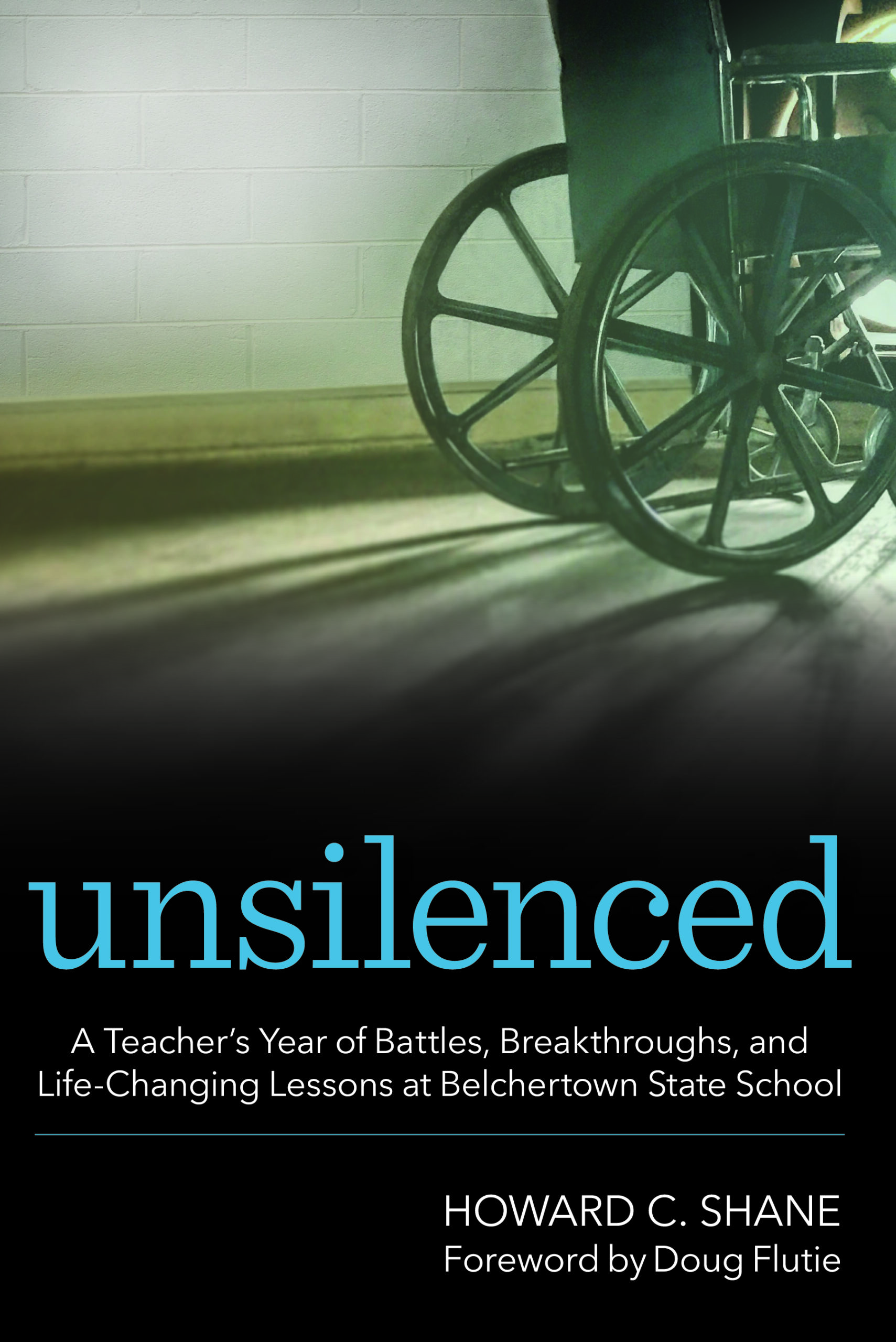

That’s just what Dr. Howard Shane does in his soon-to-be-released memoir, Unsilenced: A Teacher’s Year of Battles, Breakthroughs, and Life-Changing Lessons at Belchertown Sate School. Dr. Shane—now an internationally renowned AAC expert—transports us back to 1969, when he was fresh out of college and just starting his first teaching job at Belchertown. Young Howard is stunned by the conditions at the state school, a bleak institution where people with disabilities endure endless days of silence, tedium, and neglect. But as he gets to know his diverse and intelligent students, he becomes consumed with a mission: to unlock their communication skills and help them reach their full potential. Along the way, he butts heads with a rule-bound administrator, enjoys small victories with his students, and ends up learning just as much as he teaches.

That’s just what Dr. Howard Shane does in his soon-to-be-released memoir, Unsilenced: A Teacher’s Year of Battles, Breakthroughs, and Life-Changing Lessons at Belchertown Sate School. Dr. Shane—now an internationally renowned AAC expert—transports us back to 1969, when he was fresh out of college and just starting his first teaching job at Belchertown. Young Howard is stunned by the conditions at the state school, a bleak institution where people with disabilities endure endless days of silence, tedium, and neglect. But as he gets to know his diverse and intelligent students, he becomes consumed with a mission: to unlock their communication skills and help them reach their full potential. Along the way, he butts heads with a rule-bound administrator, enjoys small victories with his students, and ends up learning just as much as he teaches.

Today we’re honored to welcome Howard Shane to the Brookes blog to talk about Unsilenced. Read on to hear about his motivation for writing this candid and captivating memoir, his breakthrough moments, his thoughts about the future of inclusion, and more.

People write memoirs for a wide variety of reasons, so I’ll start by asking you about yours. What propelled your decision to write this book and share your early experiences at Belchertown? Is there something about today’s climate in particular that made you feel this book might be needed now more than ever?

I set out to write this memoir as a way to better appreciate the impact my Belchertown experience had on my life’s journey. As I chronicled that experience, I came to accept that my youthful enthusiasm was not ill-advised. The writing process also taught me that many of the questions I asked as a young teacher—related to best teaching practices or bettering our understanding of individuals with disabilities—remain unanswered, despite the progress we’ve made. It is the case that so many professionals from different disciplines have applied their expertise to these questions over the past few decades, and there’s no doubt we live in a more inclusive society now—but there is always more to learn and accomplish.

One lesson from that experience I haven’t amended is a continuing disdain for human warehousing that regrettably occurred throughout much of the twentieth century. I believe that sharing this story can provide an important perspective on the people who were forced to endure institutional life. And regarding today’s climate and the prospect of reopening institutions: at the end of the book is a reminder of our perpetual need to fight against the ideological pendulum that might swing back, returning us to the collective belief that institutional life is acceptable in a civilized society. We must do everything in our power to prevent that!

You’ve had a long and fruitful career as an educator and a developer of technological innovations that help people with complex communication disorders. How did your experience at Belchertown set the stage for your career and shape your future choices?

Belchertown was the catalyst for my entire professional career. When I accepted this teaching assignment, I had few life goals or direction—except an inkling that education might be a place to start. In other words, more of a hunch than a calling. The only available job in education at the time was at this state institution.

Once I settled into the job, as readers will see in the book, it consumed and challenged me in ways I had never before experienced. When I began to take note of my students’ progress, I also realized that this experience was enormously satisfying. Ultimately, my early days in the classroom unleashed a powerful internal energy that drove me to think more constructively about teaching and innovation.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t also mention the influence of Henry Peirce, the UMass professor who frequented my classroom. He was a key figure in my Belchertown days, and I talk about him quite a bit in the book. Henry became the mentor that my rudderless young self needed to accomplish what started at Belchertown and continues to this day.

Part of the book focuses on your work with your students Ron and Ruth, and your efforts to develop a device that would help them communicate. The chapter where you first get the idea to adapt the classroom clock as a communication device is so fascinating! Can you talk a little about that “aha moment” and how it unfolded?

During my early tenure at Belchertown, I became fixated on the idea of helping Ron and Ruth communicate—both of these young people possessed what you might call normal intelligence, but they were unable to speak. For some of my students, understanding was not the issue. They could understand speech as well as I could; they just couldn’t produce it. So I was constantly on the alert for something that would enable their independent symbolic expression.

When I looked at the second hand of the clock, it occurred to me: here was an electronic pointer that continuously aimed at 12 different numbers. I thought to myself, why couldn’t it simply point to words or pictures instead, and we could come up with a way for Ron and Ruth to stop the second hand when it reached the letter or picture that corresponded with what they wanted to say? That was the big aha moment for me. “And you know the rest of the story,” as the radio commentator Paul Harvey used to say.

You write with great clarity, insight, and feeling about your students and your evolving understanding of how best to teach and reach them. Of all the experiences you looked back on as you wrote this book, which one was the most emotional for you to revisit?

I describe in the book my long ride from home to visit with Ron for the last time, near the end of his life. During that drive, I tried to recall the salient events that shaped our collective experiences. It was a fifty-year timeline, and there were plenty of memories not only from our days at Belchertown but subsequent years of events in the community. But the most memorable and most heartbreaking was my final visit with Ron and his family just a day before he passed away.

When I arrived to visit him, I was escorted back to Ron’s room where he was sleeping, propped up in his bed. He woke up after a moment, as if he’d sensed me standing by his bedside, and with the help of his modern communication device, he thanked me for everything. I had to pause for a moment and wipe away a few tears before I could say what had been on my mind: “I should be the one thanking you.” Ron was the one who kickstarted my entire professional life—everyone I’ve been able to help, it was really because of the experiences I had working with Ron and his classmates. I was so glad that, during our last visit together, I was able to communicate that to him.

We’ve been getting some early feedback from college faculty members who want to add Unsilenced to their recommended reading lists, which is great. Why do you think every future education professional should read this book before entering the field?

I believe it was Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel who wrote: “The only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history.” If we don’t pay attention to where we’ve been, we run the risk of making the same mistakes in the future. Hopefully, educators who read this memoir as part of their undergraduate work will better understand that we must never go back to an institutional model—rather, we must appreciate how far we have come as educators and clinicians and keep moving forward toward greater inclusion and equity for people with disabilities.

What's the most important takeaway you hope people will come away with after reading your story? Is there a specific revelation or shift in attitude that you hope your book will spark in readers?

In the late 1970s, I recall reading “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” to my then five-year-old daughter. After discovering Snow White cleaning their cottage in exchange for a place to live, the starstruck little persons introduce themselves. Grumpy, Doc, Happy, Bashful, Sneezy, and Sleepy all happily introduce themselves, but then the six go on to say in unison, “And he’s Dopey, he never speaks.” Unfortunately, that’s an accurate reflection of the beliefs that the majority of people once held about people who couldn’t communicate in traditional ways. We’ve made some great strides since the 70s, but some people still make assumptions about the intelligence and capabilities of individuals who can’t speak. It is my hope that readers of Unsilenced learn not to instinctively equate those who are non-speaking or minimally verbal with being intellectually impaired.

The overwhelming sensation we’re left with at the end of your book is hope, although—as you acknowledge—we’re still not “all the way there” as a society in terms of disability rights and inclusion. We’ve come a long way since your days at Belchertown, but there’s still so such more progress to be made. Where do you see us going, and what do you see as the top priorities that need to be addressed in the near future?

Remarkably, it’s a fifty-year timeline from the start of the deinstitutionalization movement to the gradual and still-uncompleted acceptance of inclusion. Today, more typically developing school-age children are being educated with children having myriad developmental disabilities. The fact that people with differences are being seen and accepted as a natural part of everyday life gives me the most hope that we will eventually be an integrated society. Part of that acceptance will also occur because of the tools and opportunities that assistive technologies and ingenious medical breakthroughs will engender.

Given my long interest in applying and developing technology, I remain optimistic that leading-edge technologies will have a profound influence on the future of education for learners with special needs. For example, virtual and augmented reality will lead to clearer learner paths; wearable devices and artificial intelligence will better monitor physiological states (which will lead to better participation in inclusive classrooms); AAC devices will read brain activity, which will enable more instinctive and faster message creation; and so much more. But the future is not just about high-tech devices. I also foresee an educational and clinical workforce more willing to accept and more able to apply such advancements within the inclusive classrooms of the future.

Many thanks for Dr. Shane for stopping by the blog today to answer these questions. You can read much more about his experiences at Belchertown in Unsilenced, a book that should be required reading for every professional in the field (and every human).

Many thanks for Dr. Shane for stopping by the blog today to answer these questions. You can read much more about his experiences at Belchertown in Unsilenced, a book that should be required reading for every professional in the field (and every human).

Unsilenced

A Teacher’s Year of Battles, Breakthroughs, and Life-Changing Lessons at Belchertown State School By Howard C. Shane, Ph.D.

Nicole Eredics, author of Inclusion in Action, calls this book “a jaw-dropping reminder of how far we have come in educating individuals with disabilities and how much further we need to go.” It’s a startlingly candid look at a pivotal era in disability history—and one man’s deeply personal account of how all human beings can flourish when we care for each other and fight for change.

Stay up to date on the latest posts, news, strategies, and more!

Sign up for one of our FREE newslettersMore posts like this

15+ Recommended Resources to Help You Include and Support Students with Disabilities

September 7, 2021

13 Things Every New Inclusive Educator Should Remember

August 3, 2021

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post a Comment