Using Person-Centered Planning to Prepare Students for Employment

September 17, 2019

Person-centered planning, as defined by the PACER Center, is “an ongoing problem-solving process used to help people with disabilities plan for their future.” It’s a way to get to know students—their strengths, their needs, their goals, their dreams—and support them in creating a specific, highly personalized plan to work toward what they want.

In today’s post, excerpted and adapted from the new book Planning the Transition to Employment by Wendy S. Parent-Johnson, Laura Owens, & Richard Parent-Johnson, we’re taking a look at how to use person-centered planning to help connect students with successful integrated employment. As the authors point out, “person-centered planning is important because it is impossible to find a job match if you do not know who the person is and what they are looking for.” In this post, we share some of their strategies for getting to know your students’ interests and desires, conducting a successful person-centered planning meeting, and working on next steps.

In today’s post, excerpted and adapted from the new book Planning the Transition to Employment by Wendy S. Parent-Johnson, Laura Owens, & Richard Parent-Johnson, we’re taking a look at how to use person-centered planning to help connect students with successful integrated employment. As the authors point out, “person-centered planning is important because it is impossible to find a job match if you do not know who the person is and what they are looking for.” In this post, we share some of their strategies for getting to know your students’ interests and desires, conducting a successful person-centered planning meeting, and working on next steps.

Conduct a home visit

In Planning the Transition to Employment, the authors recommend starting by “hanging out with intent.” Set up time to visit your student, either in their home or in another environment within their neighborhood where they’re comfortable. Before or after the meeting, drive through the immediate neighborhood and make a note of relevant businesses or organizations close to the student’s home—these might be good leads when it’s time for the student to begin their job hunt.

While you’re visiting with your student, gather as much information as you can to develop a positive personal profile of the student and the ideal work environment for them. Ask person-centered questions to help reveal more about the student. Here are some sample questions, and why they might be helpful:

- “Who do you like to spend time with?” (Answers to this question can be useful when you’re developing a transition team.)

- “What do you like to do during your free time?” (Figuring out what the student likes to do can be key to helping them develop new skills.)

- “What are some things you did last year?” (This can help reveal little things that are important to the student, which may have gone unnoticed by the team members.)

- “What are you especially good at?” (Everyone has talents and gifts, and it’s best to design transition services around the person’s strengths.)

- “To be more independent, what would you like to continue working on?” (Strength-based planning allows the student to use their gifts to meet their own needs.)

- “What are some things that are extremely important to you?” (Breaking down a student’s dreams into short-term goals helps you develop clear plans toward their dreams and away from their nightmares.)

- “What community activities would enable you to pursue your interests?” (This information should be used to help the student become a part of their community.)

For students who have significant disabilities and may not be able to answer questions verbally, you might want to use pictures, videos, and direct observations to gain information. You can learn a lot from observation: facial cues, body language, and behaviors can all be indicators of preferences and interests. Observe everything, even if you don’t think it’s important—sometimes small, seemingly unimportant things can make the biggest impact on planning. Your main goal is to fully understand the student: who they are, what they want, and how you can help them reach their goals.

Hold a person-centered planning meeting

Once you’ve gotten to know your student and developed a profile of their interests, strengths, and goals, conduct a person-centered planning meeting with a variety of people who know the student best and believe in them. Here’s a brief outline of the meeting process (described in greater detail in Planning the Transition to Employment):

Decide on the guest list. First, generate a list of people to invite to the meeting. Talk to the student and create a “relationship map” to identify the most important people in the student’s life. Possible attendees could include neighbors, school or work friends, school personnel, and family members. Balance the number of professionals with nonprofessionals so the meeting doesn’t turn into a typical school meeting.

Send invitations. Work with the student to develop and send personalized invitations. Keep this activity age appropriate (e.g., using a computer or creating something in art class). Once the invitations are designed and developed, support the student in sending the invitations via email, regular mail, or in person.

Determine which questions to cover. Collaborate with the student on a list of relevant questions to cover during the meeting. Focus on the student’s interests, preferences, and needs. Your list of questions might include:

- What kind of work is the student interested in doing?

- What type of work at home or in the community has the student done in the past?

- What are the family’s work expectations?

- What are the student’s existing skills and support needs?

- What support does the student use now?

- How does the student learn new skills?

- What teaching strategies seem to work best?

Hold the meeting in a comfortable, accessible location. This first meeting should take place outside the school whenever possible—a convenient place in the community or at the student’s home.

Let the student lead as much as possible. The student should be empowered to lead the direction of the planning meeting by making meaningful choices and informed decisions.

Facilitate as much as necessary. During the meeting, serve as a facilitator to keep things running smoothly. If necessary, help the student introduce the attendees at the beginning of the meeting. Go through each of the questions on your predetermined list and be sure your group answers them all. And don’t forget to take detailed notes to help you with the next phase of planning!

Compile information and plan next steps

After the person-centered planning meeting, compile all the information you’ve gathered from the team members. Create a summary that includes the student’s goals, which action steps can help the student move to the next phase of transition planning, and who will support the student moving forward. Establish a timeline and assist the student in maintaining it.

Select transition activities to explore job options

Using the information gathered in your person-centered planning meeting, provide students with transition activities that will help them learn about different job and career options. These activities, which should be added to the student’s IEP, may include:

- Job exploration, such as career fairs, career days, and visits from local community members sharing career experiences.

- Workplace readiness activities, such as mock job interviews and job clubs with fellow students, training in financial literacy, mobility training, Skills to Pay the Bills, and social and problem-solving skill training.

- Self-advocacy instruction, including peer mentoring, setting goals, understanding and requesting accommodations, problem solving, and knowing rights and responsibilities under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and WIOA.

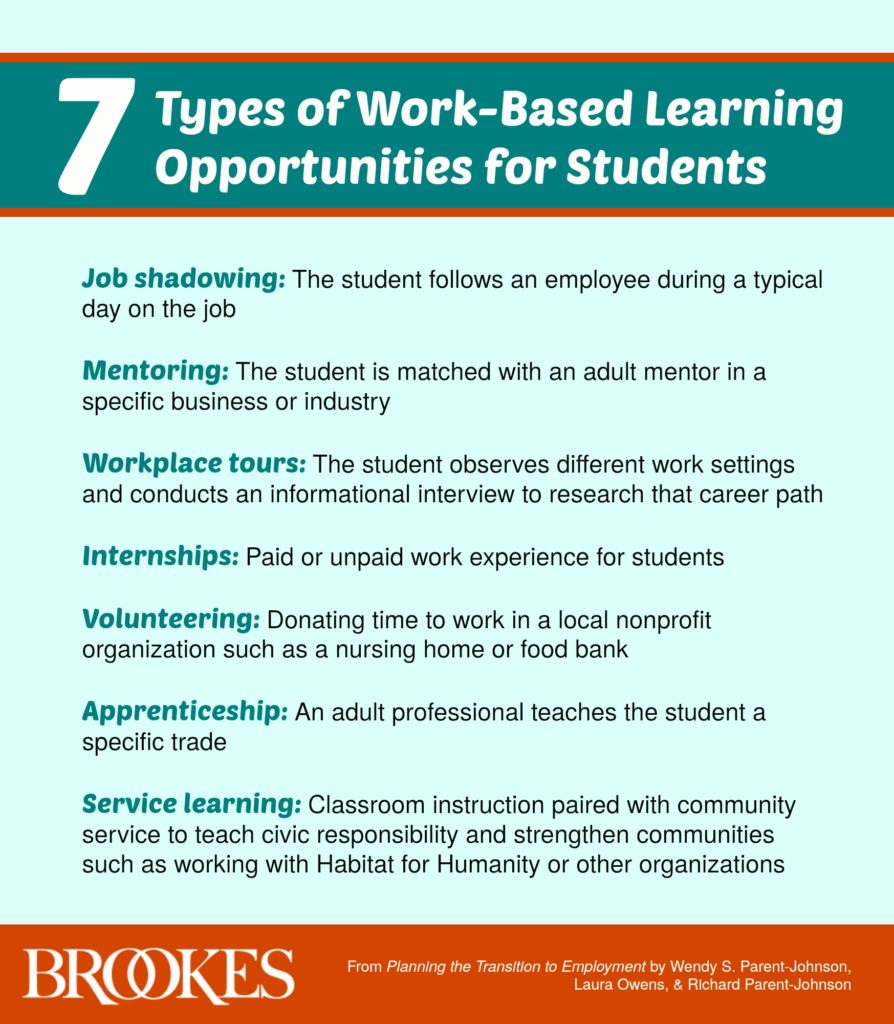

- Work-based learning that includes job shadowing, mentoring, workplace tours, paid or unpaid internships, volunteering, after-school and summer jobs arranged and supported by school staff, apprenticeships, and service learning opportunities focused on community service (see the graphic at the end of this post for a quick summary of each of these options).

- Counseling on post-secondary education options: Community college enrollment as a high school student can ease the transition to postsecondary education and can help the student become part of their community.

Help families find answers to financial questions

Financial literacy is a vital component of workplace readiness. Often, young adults with disabilities get the message to not work or work just enough to not affect their benefits. Understanding the impact work will have on benefits is essential during transition planning. If your student receives Social Security Disability or Supplemental Security Income benefits, put the student and their family in contact with a community work incentive coordinator. These are counselors specially trained to help SSI and SSDI recipients make informed choices about working. You should have information handy about Social Security Work incentives and be ready to identify work incentive specialists in your area.

This post gave you a basic introduction to preparing students for the workplace using a person-centered planning process. For more complete guidance on getting students with disabilities ready for integrated, competitive employment, check out Planning the Transition to Employment, a how-to guide that helps you empower your students to pursue the career of their choice.

This post gave you a basic introduction to preparing students for the workplace using a person-centered planning process. For more complete guidance on getting students with disabilities ready for integrated, competitive employment, check out Planning the Transition to Employment, a how-to guide that helps you empower your students to pursue the career of their choice.

SHARE THE GRAPHIC

7 Types of Work-Based Learning Opportunities for Students

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post a Comment