11 Ways to Be a Flexible, Organized, and Supportive Teacher

October 25, 2022

Flexibility, goal setting, organization, and planning are key executive function skills that have a dramatic impact on school success. Students are more likely to cultivate these important skills when they have teachers and peers who consistently model them in the classroom.

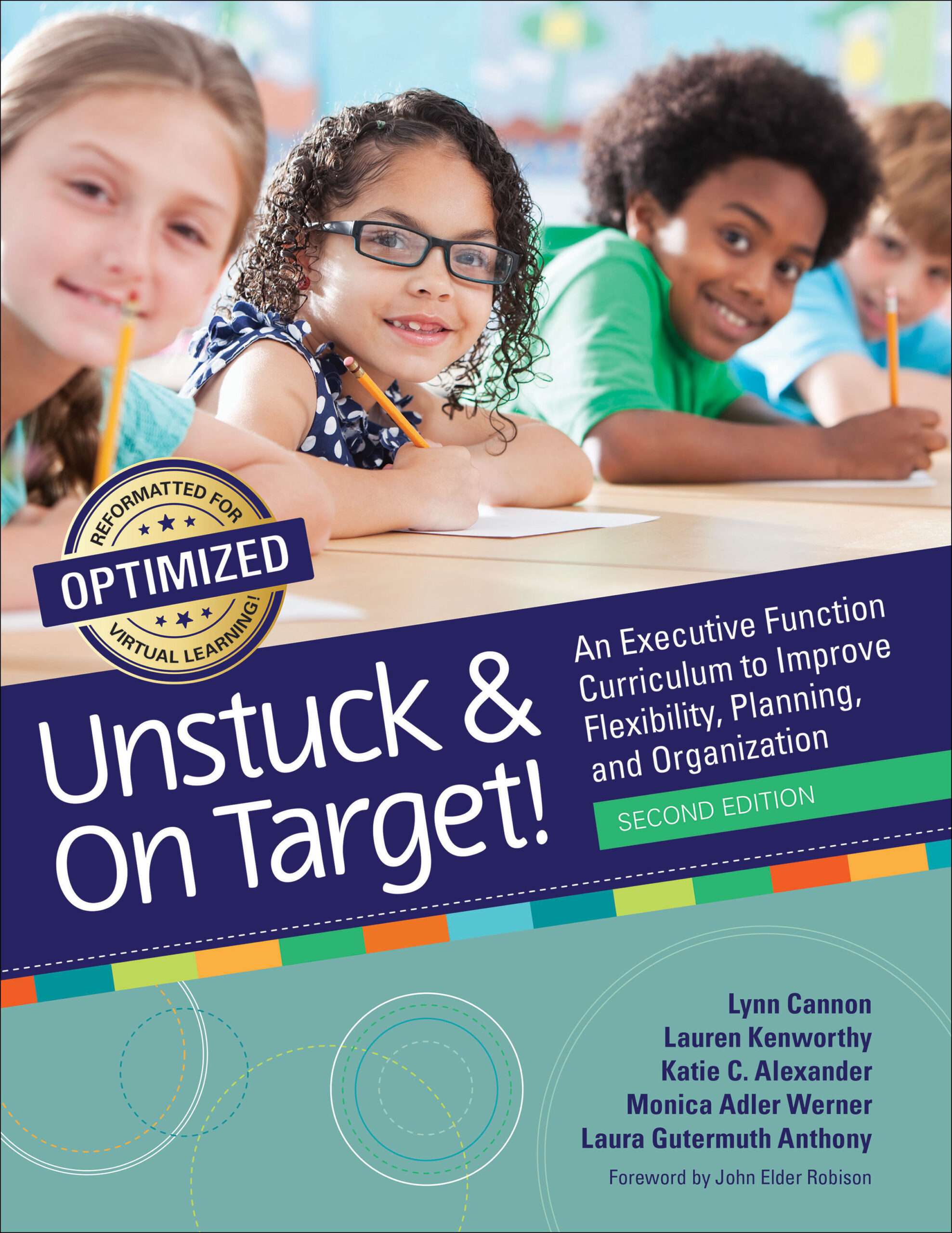

In today’s post, you’ll discover 11 ways to be a flexible, organized, and supportive teacher for all your students, including those with executive function difficulties. These tips were excerpted and adapted from Unstuck and On Target! by experts Lynn Cannon, Lauren Kenworthy, Katie C. Alexander, Monica Adler Werner, and Laura Gutermuth Anthony, a curriculum that supports executive function skills for children ages 8-11.

In today’s post, you’ll discover 11 ways to be a flexible, organized, and supportive teacher for all your students, including those with executive function difficulties. These tips were excerpted and adapted from Unstuck and On Target! by experts Lynn Cannon, Lauren Kenworthy, Katie C. Alexander, Monica Adler Werner, and Laura Gutermuth Anthony, a curriculum that supports executive function skills for children ages 8-11.

Communicate clearly and use visuals.

Communicate clearly and use visuals.

Establish explicit expectations for the work to be done, the behavior you want to see, and the ways students should set and achieve goals. Provide written step-by-step instructions for any multiple-step task, and keep whiteboards on hand to quickly “make it visual.” Provide specific visual reminders to students who have trouble following instructions and classroom routines.

Take inventory of your organization techniques. Are clutter and visual distractions minimized throughout your classroom? Are there clear routines for turning in work, getting ready to go home, and making the transition between classes? (See this blog post for specific tips on organization.)

Use a high ratio of praise to corrections (target 5:1). Praise students frequently—and before using consequences and corrections, try positive actions such as instructional scaffolding (providing the supports needed for success), elaboration (expanding on a topic to increase understanding), and modeling (demonstrating a new skill for students to learn by watching).

Use a high ratio of praise to corrections (target 5:1). Praise students frequently—and before using consequences and corrections, try positive actions such as instructional scaffolding (providing the supports needed for success), elaboration (expanding on a topic to increase understanding), and modeling (demonstrating a new skill for students to learn by watching).

Prime students for transitions. Provide active priming, or warnings that something is going to happen. To be effective, priming should occur at least several minutes before a student has to make any change, such as stopping work, changing classes, or interrupting an activity. For example, a student may have an easier time stopping a writing task if he or she is directed to finish the specific sentence they are working on and is told when they may have time to finish the activity. Model a calm demeanor during transitions between tasks, activities, and expectations, and respond flexibly when changes and unexpected events occur.

Problem-solve both internally and externally (with students) to detect when and why student performance breaks down.  For example, say that a student refuses to write a paragraph during English class. Instead of assuming noncompliance, acknowledge the student’s difficulty and work to discover why the student has refused the task. Maybe the student doesn’t know where to start, has trouble with fine motor tasks, or doesn’t have a pencil. Finding solutions and compromises (a writing rubric, providing a pencil, or allowing the student to work on a computer) are easier once a specific reason has been identified.

For example, say that a student refuses to write a paragraph during English class. Instead of assuming noncompliance, acknowledge the student’s difficulty and work to discover why the student has refused the task. Maybe the student doesn’t know where to start, has trouble with fine motor tasks, or doesn’t have a pencil. Finding solutions and compromises (a writing rubric, providing a pencil, or allowing the student to work on a computer) are easier once a specific reason has been identified.

Avoid power struggles with students. For example, when you make a request and a student refuses, refrain from making a second, more demanding request or imposing a consequence that the student refuses.

Cultivate self-knowledge. To be an effective educator, you must know yourself in the classroom. Ask yourself probing questions: What upsets you? Are there certain students or behaviors that are triggers for you? Are you ever rigid or disorganized in the classroom? When? What do you do when you are rigid? Learning your own early signs and applying strategies that work for you will increase your flexibility, organization, and efficacy.

“Think out loud” to provide a model.

Students with executive function difficulties may not realize that being flexible and setting a goal or following a plan will increase their chances of making a friend or getting better grades. These students do better when key concepts are taught explicitly and are continuously reinforced by making the implicit executive function demands of situations explicit. By highlighting your own experience of situations that require executive function skill and explicitly identifying flexible, organized responses, you can provide your students with a working framework for how they can resolve other difficult situations. For example, you might say, “I was hoping to use the projector to show you this worksheet, but the bulb is burned out. I am going to be flexible and give you each your own worksheet instead.”

These students do better when key concepts are taught explicitly and are continuously reinforced by making the implicit executive function demands of situations explicit. By highlighting your own experience of situations that require executive function skill and explicitly identifying flexible, organized responses, you can provide your students with a working framework for how they can resolve other difficult situations. For example, you might say, “I was hoping to use the projector to show you this worksheet, but the bulb is burned out. I am going to be flexible and give you each your own worksheet instead.”

Treat students with respect and as active partners in their education. Collaborative relationships do not require teachers to give in to students or give up their expectations. In fact, they often facilitate increased effort and output from students. Collaborative relationships do require a willingness to give choices within the framework of clear expectations (e.g., allowing a student to choose the topic of an essay). They also require both parties to listen to what the other has to say and take their opinions into account when appropriate.

Empower students to discover their own needs. As you identify those times of day when a student would benefit from an accommodation (e.g., taking a 5-minute reading break after lunch) or those environments that are a poor fit for the student (e.g., a loud cafeteria), support the student in discovering what they need. This is an essential first step to teaching effective self-advocacy skills. Here are two examples of what you might say:

Empower students to discover their own needs. As you identify those times of day when a student would benefit from an accommodation (e.g., taking a 5-minute reading break after lunch) or those environments that are a poor fit for the student (e.g., a loud cafeteria), support the student in discovering what they need. This is an essential first step to teaching effective self-advocacy skills. Here are two examples of what you might say:

“I noticed that the cafeteria is very loud and you cover your ears when you are in there. That makes it hard for you to talk or eat your food. Can you help me think of a spot that would be less noisy where you could have lunch?”

“You have told me that you are really tired when you come in the morning. After you went on the swings yesterday you had a lot more energy and you were able to start your work. What strategy should we use when you come in feeling tired in the morning?”

Provide an optimal level of support through just-right cuing techniques. Use guided practice with faded cuing to gradually build new skills, one step at a time. Guided practice begins with concrete tasks and a high level of teacher support (i.e., verbal prompting and redirection). Keep in mind that the role of the adult is to scaffold behavior only as much as the student needs in order to be successful, not to serve as a crutch or to create a dependency. Gradually fade your support and guidance as soon as students can demonstrate the skill independently.

Use the guidance in today’s post to help improve outcomes for your students with executive function difficulties. And for a complete, field-tested curriculum on teaching cognitive flexibility and goal-setting, check out the Unstuck and On Target! kit for elementary schools (middle school and high school versions are coming soon!).

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post a Comment