Prepping a Universally Designed Classroom: Beth’s UDL Story

May 23, 2017

UDL fans (and the UDL-curious among you): we’ve got a great post for you today.

Over the past few years, we’ve done a bunch of UDL posts on getting started, busting through mental barriers, lesson planning, and supercharging traditional teaching strategies with UDL. But we haven’t written a lot about the actual prep work that goes into a universally designed classroom—so today we have a really good case story that takes you through one teacher’s planning process.

Here’s what Beth, a fourth-grade teacher, does to create an accessible, universally designed classroom that incorporates all three UDL principles: multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement. Excerpted and adapted from the book Teaching Everyone by Whitney Rapp and Katrina Arndt, this to-do list maps Beth’s journey toward a universally designed environment that welcomes all learners and helps every one of them succeed. Hope it gives you some good ideas you can use in your own classroom next year!

Write an introductory letter. Beth begins with an introductory letter to her students and their families. The letter introduces herself as a teacher, mom, and lifelong learner. It lets them know what to expect the first few days of school and during the whole school year—the friends they will make, field trips they will take, and goals they will accomplish together. Beth invites the students and families to visit the classroom in mid-August, before the year begins. She makes copies of the letter in every language spoken in the homes of students in her district.

Read up on students. Beth takes a look at the roster for the upcoming school year. She has a diverse class of 10 boys and 11 girls. Seven students have IEPs, two have Section 504 plans, four students have two households listed due to joint custody arrangements, one student lives with grandparents, three students have same-sex parents, and one student speaks Russian as her first  language. Beth practices saying each name aloud, making a note to ask children to clarify pronunciation and preferred nicknames.

language. Beth practices saying each name aloud, making a note to ask children to clarify pronunciation and preferred nicknames.

Next, Beth looks at each student’s folder, reading last year’s report cards as well as each IEP and 504 plan. She likes to read the information so she can be prepared, but she doesn’t think the files could ever tell her everything there is to know about her students. The files provide her with just enough information to determine an initial classroom arrangement that will respond to many different learning needs.

Arrange desks thoughtfully. Beth decides to arrange the student desks into pods of six around the Smart Board she uses for direct instruction. The pods are arranged so that no student’s back is to the Smart Board, and they’re conducive to variable grouping, so it’ll be easy for students to work in small groups, individually, or in pairs. Beth makes sure she has room to converse with each student at their desk without disturbing the others in the pod. The kidney-shaped table in Beth’s room will be used primarily for guided reading groups and can double as a breakout workspace when reading groups aren’t in session.

Beth places her teacher desk near the Smart Board so she can access teaching materials quickly during direct instruction without getting in the way of classroom traffic (she rarely sits there when class is in session). There’s an extra student desk, which she places in a light traffic area near her own desk. It offers another place for students to choose to complete independent work.

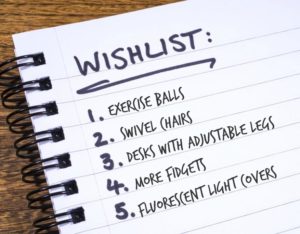

Make a classroom supply wish list. Beth thinks about her “wish list” of classroom supplies. The first thing on her list is various seating alternatives. She would love to have a few exercise balls  for kids who wiggle while they work, and she can think of a few students who would benefit from swivel chairs so they can see any wall in the classroom without changing how they are seated in the chair. Also, she wishes the desks could be better adjusted for size. The current desks have one or two height settings in the legs, but the width and depth should vary, too. She makes her list, to be fulfilled as her school’s budget allows.

for kids who wiggle while they work, and she can think of a few students who would benefit from swivel chairs so they can see any wall in the classroom without changing how they are seated in the chair. Also, she wishes the desks could be better adjusted for size. The current desks have one or two height settings in the legs, but the width and depth should vary, too. She makes her list, to be fulfilled as her school’s budget allows.

Arrange classroom areas strategically. Beth arranges her classroom so she can see every area clearly and has an accessible place for everything she needs during the day. She walks around the classroom several times, taking a different path each time. There’s plenty of room among the pods and other furniture for comfortable mobility. This arrangement will change once students enter and Beth determines what these learners need, but this is a great starting point.

Don’t forget a quiet book area. Beth’s favorite spot is the quiet area. Partially nestled in a nook under overhead storage shelves, the quiet area includes a soft rug, giant pillows, beanbag chairs, and upright chairs. The area is surrounded by bookcases that hold a vast range of books and isolate the nook from much of the classroom stimuli. There are books at all reading levels. Beth makes sure there are books on many different topics that reflect the interests of her students, as well as culturally relevant books that respond to a range of experiences.

Make sensory adjustments. Because some of her students have experienced sensory processing difficulties with respect to lighting, Beth has fluorescent light bulbs removed over one pod of  desks. There’s still enough light to read by, but the glare and hum of the lights are much reduced. Each chair leg in the classroom is equipped with a tennis ball fitted over the end, and Beth inspects them and replaces any loose or worn-out tennis balls (she makes a note to revisit the nearby tennis club to see if they have another used batch of balls for her). Next, she cleans her box of fidget toys—a sand-filled balloon, a Rubik’s Cube, a hacky sack, a golf ball, and more. She’s found that many students can sustain attention longer if they handle a fidget toy during class. Some teachers won’t use them because of the potential distraction, but she’s found that students are less distracted when fidgets are available.

desks. There’s still enough light to read by, but the glare and hum of the lights are much reduced. Each chair leg in the classroom is equipped with a tennis ball fitted over the end, and Beth inspects them and replaces any loose or worn-out tennis balls (she makes a note to revisit the nearby tennis club to see if they have another used batch of balls for her). Next, she cleans her box of fidget toys—a sand-filled balloon, a Rubik’s Cube, a hacky sack, a golf ball, and more. She’s found that many students can sustain attention longer if they handle a fidget toy during class. Some teachers won’t use them because of the potential distraction, but she’s found that students are less distracted when fidgets are available.

Schedule classroom visits. Beth knows some students need to be prepared ahead of time. They need to know what the classroom looks like, what their teacher is like, and where they’ll sit the first day. Doing her part to relieve that anxiety is one more way she creates an accessible classroom for all students. Beth spends the middle of August meeting with new students and their families, and those initial visits contribute to the yearlong process of gathering valuable information about her students.

The new school year starts—and by November, Beth’s classroom is a true community. The class has signed a class constitution, completed buddy projects  around the school’s character-education qualities, collaboratively built toothpick and marshmallow towers to see how different groups come up with different processes and products, formed bonds with their homework buddies, and put together a time capsule of their favorite things to revisit at year’s end. Community connections have been established with high school students in a homework club and guest speakers who come to the classroom to talk about the importance of education in various careers.

around the school’s character-education qualities, collaboratively built toothpick and marshmallow towers to see how different groups come up with different processes and products, formed bonds with their homework buddies, and put together a time capsule of their favorite things to revisit at year’s end. Community connections have been established with high school students in a homework club and guest speakers who come to the classroom to talk about the importance of education in various careers.

All of Beth’s lessons are auditory, visual, and hands-on in some way, and the students master many  different ways of showing what they know. They give oral reports, write papers and poems, create artifacts, and use various software programs. All students have become comfortable supervising morning business tasks, using the Smart Board for writing and printing notes and running video clips, and making use of the breakout areas in the room. The classroom AT repertoire now also includes laptops for students who type instead of write by hand, video cameras for creating motion pictures or capturing field trips, and tape recorders for creating books on tape.

different ways of showing what they know. They give oral reports, write papers and poems, create artifacts, and use various software programs. All students have become comfortable supervising morning business tasks, using the Smart Board for writing and printing notes and running video clips, and making use of the breakout areas in the room. The classroom AT repertoire now also includes laptops for students who type instead of write by hand, video cameras for creating motion pictures or capturing field trips, and tape recorders for creating books on tape.

Beth uses many different strategies to meet her all her students’ needs, adjusting her strategies as the year goes on. One learner uses a desktop checklist to get through his work each day. A student who is color-blind benefits from new fidgets, locker checklists, and folder labels. Everything in the room is labeled for students who are English language learners. Music plays at transition time while the Smart Board displays a visual timer, and a few minutes of daily yoga helps increase focus and time on-task. Problems arise sometimes, but Beth always finds time to collaborate with teachers, administrators, and families to brainstorm solutions.

Beth’s classroom is a great example of a community that’s universally designed for learning. All three UDL principles are at work: multiple means of representation, action and expression, and engagement. All her students are valued for their uniqueness, strengths, and weaknesses, and every learner feels safe taking risks and making mistakes.

***

Get more in-depth, practical advice on UDL, classroom community, accommodations and modifications, and much more in Teaching Everyone by Whitney Rapp and Katrina Arndt.

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

comments

Kathleen says

This has been very helpful, as I'm learning as a third-year teacher how to use UDL in the classroom for my students.

Kathleen-alstyne2010@gmail.com.

jlillis says

So glad you found this post useful!

SHARON BROOKS says

Learning Tools are always helpful

Post a Comment