13 Ways to Support the Behavior and Learning of Students on the Autism Spectrum

January 16, 2018

[POST UPDATED on 2/23/22]

In your inclusive classroom, how can you best address the academic and behavioral needs and challenges of learners on the autism spectrum?

There’s no formula or recipe to follow, since every student—with or without an identified disability or disorder—is unique. You’ll likely notice that some students on the autism spectrum respond well to your preventative supports for the whole class, such as setting and explicitly teaching clear expectations, providing reinforcement when students meet expectations, and using consequences that help redirect the student to desired behavior (if you’re using a multi-tiered system of supports, these would be Tier 1 supports). For other learners, you may need to try additional, Tier 2 interventions to address their needs and help them meet their goals.

There’s no formula or recipe to follow, since every student—with or without an identified disability or disorder—is unique. You’ll likely notice that some students on the autism spectrum respond well to your preventative supports for the whole class, such as setting and explicitly teaching clear expectations, providing reinforcement when students meet expectations, and using consequences that help redirect the student to desired behavior (if you’re using a multi-tiered system of supports, these would be Tier 1 supports). For other learners, you may need to try additional, Tier 2 interventions to address their needs and help them meet their goals.

In today’s post, we offer 13 evidence-based and research-supported practices for strengthening the academic and behavioral skills of students on the autism spectrum. These suggestions are excerpted and adapted from Behavior Support for Students with ASD by Debra Leach, a new guidebook that shows you how to address ten of the most common classroom behavior challenges. (You’ll find that many of these ideas help all learners in your classroom, too!)

Use Concrete Examples

When teaching new skills to students on the spectrum, use concrete examples before moving directly into teaching abstract concepts. This is important because students on the autism spectrum often think literally. Try using manipulatives and models, and connect abstract concepts to things that are familiar to the student. For example, if you’re talking about conduction, you might bring in a pan and talk about what would happen if you touch the pan when it is hot (instead of relying on a definition and one or two verbal examples).

Provide Visual Supports

Many students on the spectrum benefit from visual supports to promote their learning and positive behavior. Get creative and develop visual supports that meet your students’ specific needs. You might try activity schedules enhanced with photos or illustrations, graphic organizers, symbols, charts and graphs, maps, cue cards, scripts, and visual boundaries. (This blog post has 7 ideas for visual supports that may be helpful.)

Follow the Student’s Lead

This is a good strategy to use with students who have significant deficits in joint attention. Initiate engagement with something your student is focused on to establish joint attention and reciprocal exchanges. You can also follow the student’s lead by positively responding to comments the student makes and questions they ask during group instruction, even if they seem off topic. Try to find a way to respond that acknowledges the ideas shared by the student but also connects to the lesson.

Use Motivational Strategies

To increase motivation in your students, consider these strategies:

- Tap into fascinations. Some learners on the autism spectrum have a restricted range of interests and find school lessons and activities uninteresting. Shift to a strengths- and interest-based model in which your instruction uses the natural fascinations of your students as teaching tools. (The book Just Give Him the Whale! by Kluth & Schwarz is packed with creative strategies for working students’ strengths and interests into your lessons.)

- Start with easy tasks. Academic success is a great natural reinforcer for all students. Before each difficult task, start out by presenting two or three easy tasks for students to complete first. Your students will be reinforced and motivated by this quick success, and they’ll build the momentum they need to attempt a more challenging problem.

- Increase choices to increase motivation. Some challenging behaviors are rooted in a need for control. To satisfy this need and increase motivation, provide as many opportunities as possible for students to make choices throughout the school day. For example, allow them to choose study topics, materials, or ways to learn new material; select partners for group activities; or decide how to demonstrate their learning (e.g., by writing an essay, answering multiple-choice questions, drawing a picture, or giving an oral response).

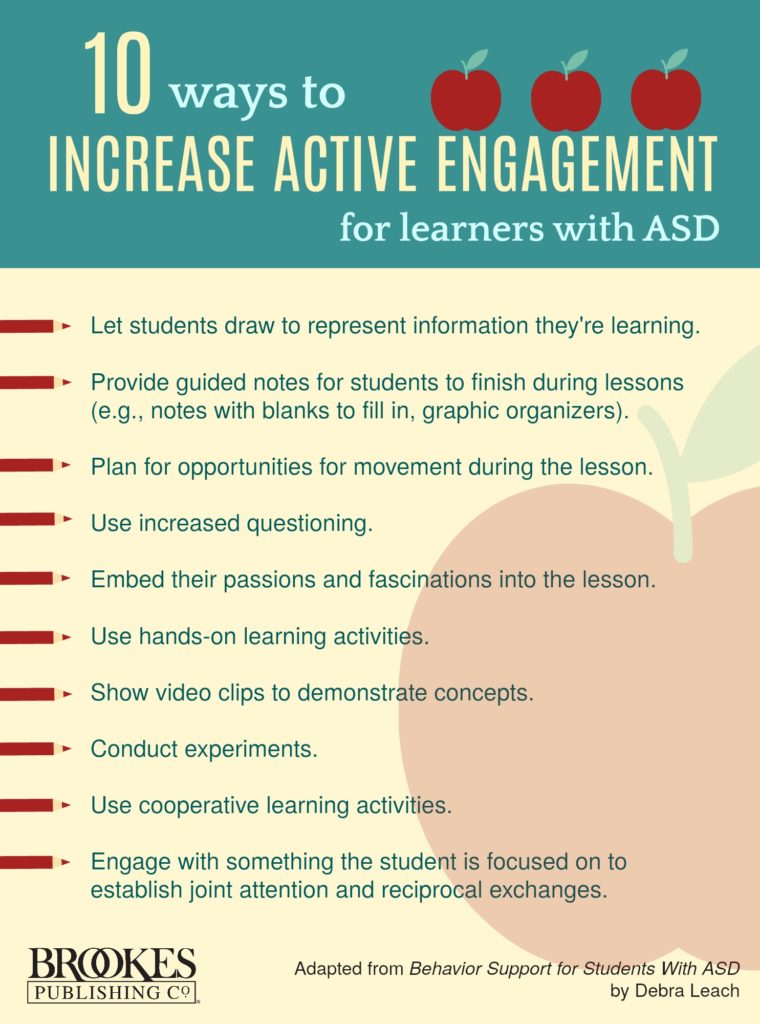

Increase Active Engagement

For many students, it can be a big challenge to simply sit at their desks and absorb new information. Most students learn faster and better when they’re actively engaged in instructional activities (and engagement helps reduce challenging behavior, too). Here’s a graphic with 10 ways to boost your students’ active engagement:

Arrange the Environment to Address Student Needs

Do your students seem overwhelmed by stimuli in your classroom? Think about how you can adjust the learning environment for your students who have sensory processing or emotional regulation issues. You may want to:

- modify lighting if overhead fluorescents cause discomfort or overstimulation

- remove excess clutter from the bulletin boards and the classroom in general

- create a safe space or “cool down area” students can use if emotionally distressed

- give preferential seating to students who have difficulties with focus and attention

- provide clearly defined work spaces

- use an emotional thermometer or rating scale to help students identify their emotional states and choose coping strategies to implement

- explore ways to reduce noise in the classroom (this article from Paula Kluth has some good suggestions on how to help students who struggle with noise).

Use Prompting and Fading Procedures

Prompting and fading strategies can help students learn and master new skills. Some examples are:

- Modeling/request imitation: Show the student what to do and immediately give the student a chance to imitate your model and get feedback.

- Least-to-most prompting: Begin with the least intrusive prompt you think the student needs to be successful and increase the prompting supports if necessary. Gradually fade supports once the student can respond independently.

- Most-to-least prompting (graduated guidance): Begin with intensive prompting and fade it out with successive opportunities.

- Time-delay: Systematically wait for a student to respond before delivering a prompt, in order to decrease the student’s dependence on the prompt.

For more guidance on using prompting and fading strategies, see this book by Debra Leach.

Prepare Students in Advance

How many of your students get anxious and fearful when a change in your normal routine happens? To help students cope, prepare them in advance of the change by arming them with reassuring information. Explain the upcoming change verbally, in writing, or using social narratives—whatever works best for your students.

You can also use this strategy to prepare students for upcoming lessons and activities. Preteach skills and concepts in small-group or one-to-one contexts before an upcoming whole-group lesson. Then when the actual lesson takes place, the student will already have a basic understanding of the lesson format and content, which may reduce the likelihood of frustration and challenging behaviors. (It’s a good idea to get parents involved in preparing the student at home for an upcoming lesson or schedule change. Send a note home explaining how they can help!)

Break Down Multistep Assignments into Steps

Because many students have issues with executive function skills, they often need supports when learning how to complete multistep assignments. You can use strategies like task analysis, self-monitoring, and video modeling to address this need.

Task analysis involves breaking complex assignments or directions down into simple, sequential steps and then teaching the steps until your student can put it all together and complete the entire task independently.

Self-monitoring tools can be used to provide a visual representation of the individual steps of the task (either in words or pictures). Students can check off each step as it is completed.

Point-of-view video modeling involves showing a video clip of the task being performed from the student’s perspective. This strategy can be very effective for students with focus or attention problems, because the clip removes extraneous information and focuses solely on the steps of the task.

Be Careful Not to Reinforce Challenging Behavior

When students engage in challenging behavior, it’s a natural impulse to respond negatively by reprimanding the student, removing them from the activity or classroom, or delivering other punitive consequences. But you’ve probably already seen how consequences intended as punitive can actually operate as positive reinforcement for some students. They may be seeking attention, or they may enjoy your predictable reactions due to their need for sameness. In cases like these, students will quickly learn that challenging behavior is the most efficient way to get your attention.

To address this issue, try using differential reinforcement in your classroom. In a nutshell, this means you refrain from reinforcing challenging behaviors while increasing your positive reinforcement for desirable behaviors. There are many ways to use differential reinforcement; this article provides a good introduction and some brief examples, and this page includes more extensive examples and a list of additional resources.

Teach Communication Skills

Students on the autism spectrum may engage in challenging behavior because they aren’t equipped with the functional communication skills they need to express themselves in various situations. They may not naturally learn how to say essential phrases like, “I don’t know,” “Can you help me?” “What do you mean?” “I don’t feel well,” or “I can’t do this right now.” To help students express their needs, explicitly teach helpful communication skills based on their individualized needs.

Provide Expressive Communication Supports

For students who experience challenges with expressive communication skills, augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) can help them meaningfully participate in academic and social activities. AAC can be low tech or high tech:

Low-tech AAC includes communicating using arrays of pictures or symbols, response cards, and simple switches with prerecorded words or messages.

High-tech AAC includes communication devices such as the Dynavox or apps on the iPad or other tablets.

An assistive technology evaluation can help determine which AAC supports are best for your student. For more support, contact the AT specialist(s) in your school district or state.

Consider Peer Supports

Students on the autism spectrum often need support in many areas, and educators can’t always provide all of those supports at the moment they’re needed. Peers can be a great source of supplemental support, if they receive effective training on peer-mediated interventions. Provide guidance to peers on strategies and approaches they can use to engage students and encourage their use of social reciprocity skills. (To get you started, there’s a learning module on peer-mediated interventions on this website.)

***

Often, you’ll find it’s most effective to use two or more of these strategies together when you’re planning and implementing interventions. Tailor the combination of strategies to your student’s specific needs—and if you have a success story to share, we would love to hear from you!

GET THE BOOK

Find out how to address ten of your most common classroom behavior challenges—from following directions to handling transitions—with skill, insight, and compassion.

Find out how to address ten of your most common classroom behavior challenges—from following directions to handling transitions—with skill, insight, and compassion.

LEARN MORE

You can find learning modules for the strategies discussed in this blog post at the Autism Internet Modules website.

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post a Comment