5 Characteristics of Effective Structured Literacy Teaching

September 22, 2022

At Brookes, we believe in the power of structured literacy instruction to prepare students for reading success. We partner with some of today’s most celebrated experts—including Speech to Print author Louisa Cook Moats, Ed.D.—to bring you the best resources on aligning your teaching with the science of reading.

At Brookes, we believe in the power of structured literacy instruction to prepare students for reading success. We partner with some of today’s most celebrated experts—including Speech to Print author Louisa Cook Moats, Ed.D.—to bring you the best resources on aligning your teaching with the science of reading.

Excerpted from the third edition of Speech to Print, today’s post outlines five essential characteristics of high-quality structured literacy teaching: explicit, systematic, cumulative, multimodal, diagnostic and responsive, and multilinguistic.

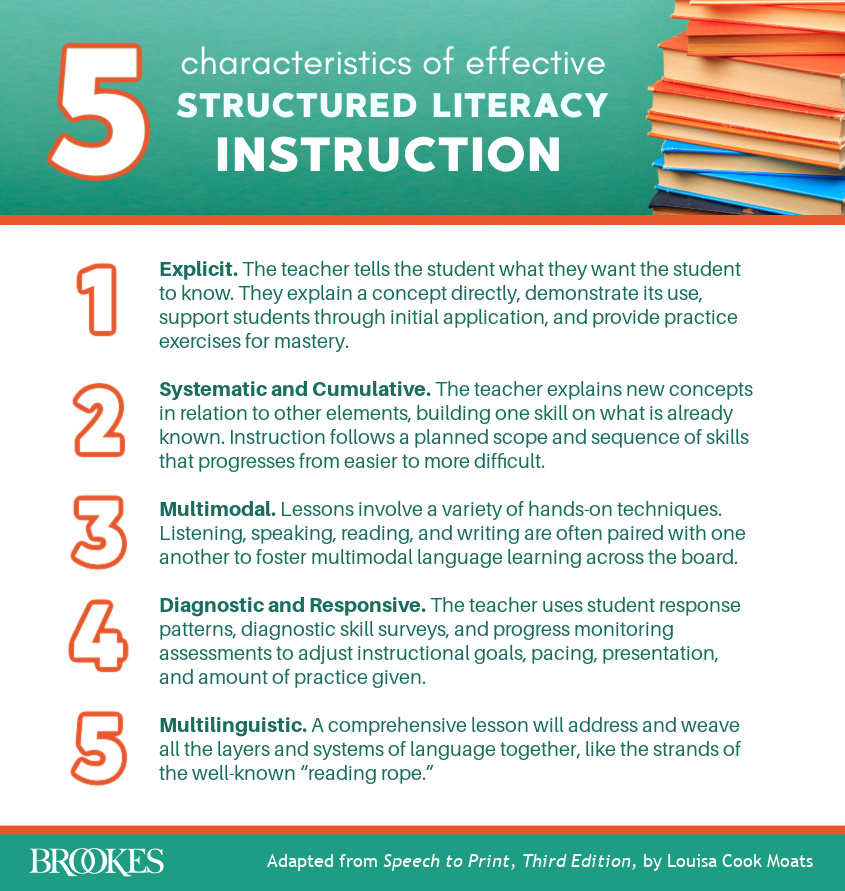

Explicit

Explicit teaching means the teacher tells the student what she wants the student to know. She explains a concept concisely and directly, demonstrates its use (“I do”), supports students through initial application (“we do”), and then provides practice exercises (“you do”) sufficient for mastery.

Lessons often employ familiar instructional routines to pick up the pace and promote student engagement. For example, hand signals and verbal cues might support sound blending, while minimizing extraneous talk from either the teacher or the students. During practice, students receive immediate corrective feedback. Discovery learning of language structure is deemphasized until the student has the competence and tools to attend to linguistic detail and detect patterns.

Explicit teaching is briskly paced and frequently elicits student responses. Students should have many opportunities to verbalize the sounds, words, and concepts of the lesson, to read and write examples of concepts that have been taught, and to read aloud.

Systematic and Cumulative

Systematic teaching means the teacher explains new concepts in relation to other elements of the system being taught, building one skill or concept on what is already known. For example, if the new concept is the oi/oy spelling alternation, the teacher might place this information in the context of the English writing system more generally, noting that other such alternation patterns exist and that words in English generally do not end in the letter i.

Instruction follows a planned scope and sequence of skills that progresses from easier to more difficult. The goal of systematic teaching is automatic and fluent application of language awareness to word, sentence, and passage reading and writing.

Multimodal

To increase focus and fully engage students in the tasks, lessons involve hands-on techniques, such as moving tiles into sound boxes as words are analyzed; using hand gestures to support memory for sounds; building words with letter, syllable, or morpheme tiles; assembling sentences with words on cards; color coding sentences in paragraphs; and so forth. The Orton-Gillingham approach routinely uses a practice drill linking letter naming, keyword naming, letter writing, and letter– sound association. Listening, speaking, reading, and writing are often paired with one another to foster multimodal language learning across the board.

Diagnostic and Responsive

The teacher uses student response patterns, diagnostic skill surveys, and progress monitoring assessments to adjust instructional goals, pacing, presentation, and amount of practice given within the lesson framework. The teacher monitors progress through observation and brief quizzes that measure retention of what has been taught. Lessons are modified accordingly.

Multilinguistic

The layers and systems of language comprise the content of lessons. A comprehensive lesson will address and weave these together, like the strands of the reading rope. The reason for including all layers of language is to deepen lexical knowledge and grammatical knowledge and thereby foster more fluent processing of print.

- Phoneme awareness. Until students are proficient readers and competent spellers, lessons should include activities designed to sharpen awareness of individual speech sounds, syllable stress patterns, and advanced phoneme manipulation. These are independent of, but connected to, print-based activities.

- Sound–symbol (phoneme–grapheme) correspondences for reading and spelling. Approximately 75 to 90 phoneme–grapheme correspondences are frequent enough that they can be directly taught and practiced, over a period of 1 to 3 years.

- Orthographic patterns and conventions, beyond predictable phoneme– grapheme relationships. Spellings such as –ck, –tch, and –dge after short vowels, or the constraints on letters v and j, should be taught. Familiarity with the six basic types of written syllables helps students decode and spell vowel sounds: closed (com, mand), open (me, no), vowel-consonant-e (take, plate), vowel team (vow, mean), vowel-r combinations (car, port), and the final consonant-le pattern (lit-tle, hum-ble).

- Morphology. The consistent and stable spellings of morphemes, including prefixes, roots, base words, and suffixes, provide keys for word reading, vocabulary, and spelling. Instruction in morphology can be linked to words’ grammatical roles and language of origin, in cases where that information will help explain why words are spelled the way they are.

- Syntax. The study of syntax helps students understand and express meaning in relation to word order and sentence structure. It includes understanding parts of speech and conventions of grammar and word use. Lessons include interpretation and formulation of simple, compound, and complex sentences, and manipulation of phrases and clauses in sentence construction.

- Semantics. Meaning should be sought and discussed at the word, phrase, sentence, and discourse levels, with teacher modeling and guidance. Even in beginning instruction with simple words, semantic relationships such as multiple meanings can be explored.

To summarize, comprehensive, structured literacy instruction includes time for development of all language skills on which word recognition and language comprehension depend. While foundational skills are being learned, students at all levels can be exposed to many kinds of texts—stories, informational text, poetry, drama, and so forth, even if that text is read aloud to them. Familiarity with academic language will become more important to reading comprehension as a student gains basic reading skills. Reading worthwhile texts that enrich vocabulary and stimulate deep thinking about important ideas is a critical component of any English language arts program.

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post a Comment