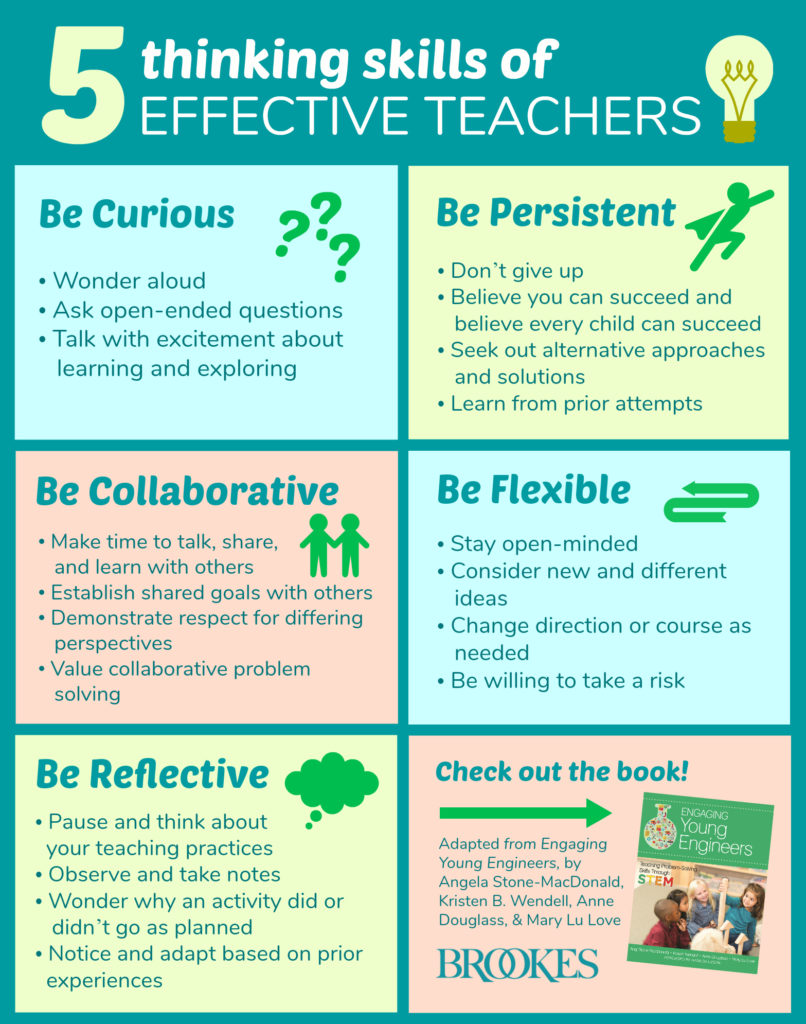

5 Thinking Skills of Effective Teachers

August 27, 2019

Today’s blog post shines a light on five essential thinking skills that the most effective teachers have. A quick glance at the list will tell you these are all skills that good teachers try to cultivate in their students—but they’re equally important for educators to nurture in themselves. Read the post (excerpted and adapted from Engaging Young Engineers by Angela Stone-MacDonald, Kristen B. Wendell, Anne Douglass, and Mary Lu Love), and then think about how you can model these qualities in your own classroom this year.

Today’s blog post shines a light on five essential thinking skills that the most effective teachers have. A quick glance at the list will tell you these are all skills that good teachers try to cultivate in their students—but they’re equally important for educators to nurture in themselves. Read the post (excerpted and adapted from Engaging Young Engineers by Angela Stone-MacDonald, Kristen B. Wendell, Anne Douglass, and Mary Lu Love), and then think about how you can model these qualities in your own classroom this year.

Curiosity

Curiosity is one of the most important foundational qualities a young learner can have; it sparks exploration, prompts students to ask questions and seek answers, and sets the stage for cognitive development. But curious thinking is just as important for teachers.

Curiosity is one of the most important foundational qualities a young learner can have; it sparks exploration, prompts students to ask questions and seek answers, and sets the stage for cognitive development. But curious thinking is just as important for teachers.

Simply put, a curious teacher is someone who asks questions and wonders. When a student presents a challenge in the classroom or has trouble in a particular subject, curious teachers ask themselves good questions and seek innovative solutions to the problem. Teachers should also explicitly model curiosity in the classroom by asking students open-ended questions and wondering out loud “what will happen if…?”

Teachers who demonstrate curious thinking for students are creating learning environments full of excitement, exploration, and imagination. They’re also communicating how essential curiosity is to the process of problem-solving, which will help young learners become young innovators.

Persistence

Every teacher wants their students to be persistent. How many times have you said some version of “don’t give up!” or “keep trying” in the classroom? Persistence is an invaluable trait for teachers to cultivate, too, especially when you’re working in an inclusive classroom with students who have a wide range of needs and behaviors. Teaching children is a complicated art, and a single approach or strategy isn’t going to work with every child. Show your persistence by maintaining high expectations for all students, not giving up when your first (or second, or third) strategy for engaging a child doesn’t work, and trying new strategies until you and your student succeed.

Every teacher wants their students to be persistent. How many times have you said some version of “don’t give up!” or “keep trying” in the classroom? Persistence is an invaluable trait for teachers to cultivate, too, especially when you’re working in an inclusive classroom with students who have a wide range of needs and behaviors. Teaching children is a complicated art, and a single approach or strategy isn’t going to work with every child. Show your persistence by maintaining high expectations for all students, not giving up when your first (or second, or third) strategy for engaging a child doesn’t work, and trying new strategies until you and your student succeed.

To model persistent thinking for your students, let them see you trying new things in the face of a challenge. Talk through it to show them how you’re not giving up. Explicitly teach your students the following key lessons about persistence:

- Persistence means trying again and often trying a new or different approach.

- Persistence can result in improvement and success.

- Persistence also relies heavily on reflection. When we try again and again, we don’t just repeat the same approach over and over. We reflect on our approach to inform the next attempt. (See #4 on today’s list for more on the importance of reflection.)

Flexibility

Every teacher’s been there at least once: An outdoor drama activity must be moved indoors when a thunderstorm suddenly rolls in. A lesson is upended when the overhead doesn’t work, or a laptop’s sound cuts out. Even the best-planned activities get disrupted by the unexpected—and when curveballs strike, flexibility is key for both teachers and students.

Every teacher’s been there at least once: An outdoor drama activity must be moved indoors when a thunderstorm suddenly rolls in. A lesson is upended when the overhead doesn’t work, or a laptop’s sound cuts out. Even the best-planned activities get disrupted by the unexpected—and when curveballs strike, flexibility is key for both teachers and students.

So how can you engage in more flexible thinking and model it for your students? Here are two ideas:

- One way you might model flexibility is by thinking out loud as you adapt an activity. For example, if your outdoor stage production needs to relocate to the classroom due to rain, walk your students through your thought process as you decide where the new stage will be, where people will sit, and how to improvise a curtain. This kind of self-talk not only helps you organize your thoughts and keep moving forward, it also shows students exactly what flexibility looks and sounds like in action.

- Another way to demonstrate flexible thinking is to involve students in solving a problem that’s unexpectedly come up. Encourage the children to suggest many possible responses to a question or a problem rather than looking for just one answer. A key element of flexible thinking is the awareness that there’s almost always more than one way to solve a problem.

Reflection

We teach students about the importance of reflection: taking the time to step back from their work and evaluate what did and didn’t work. Reflection is an equally important process for teachers, since it informs how you differentiate and adapt your instruction for individual learners.

We teach students about the importance of reflection: taking the time to step back from their work and evaluate what did and didn’t work. Reflection is an equally important process for teachers, since it informs how you differentiate and adapt your instruction for individual learners.

Regular reflection should be a natural part of your teaching process—and it probably already is. If you’re like most teachers , you already take the time to step back from your practice, ask yourself questions, and reflect on what you could do next to solve persistent challenges. You may even take observational notes on your students and reflect on them regularly. But most of the time, this kind of reflection is done in private or with other adults, which means that students miss out on seeing this essential skill modeled in the classroom.

How can you make reflection more visible to children and model this thinking process for them? One thing to do is think and wonder out loud (the kind of self-talk suggested in the section on flexible thinking). For example, you might reflect with your class on how much they all liked the informational book you read yesterday about fire engines. Wonder out loud how your class can learn more about fire engines, and whether they might be interested in visiting the local fire station or inviting a firefighter to visit the class. Ask questions about what they might learn from each type of experience, and encourage the students to reflect on other ways they can learn more about the subject.

Collaboration

All teachers want their students to learn how to work together peacefully and productively. Collaborating with others toward a shared goal is an essential skill for teachers, too. Partnering up with your colleagues regularly to reflect together about problems can help you develop new approaches and solutions you might not have thought of on your own.

All teachers want their students to learn how to work together peacefully and productively. Collaborating with others toward a shared goal is an essential skill for teachers, too. Partnering up with your colleagues regularly to reflect together about problems can help you develop new approaches and solutions you might not have thought of on your own.

Hone your collaborative thinking skills by joining or starting a multidisciplinary team that comes together to share, reflect, and plan for how to support an individual child. If you’re a co-teacher, plan special collaboration times when the two of you can sit down and work through an issue you’re having in the classroom (and be sure to model your collaboration skills for your students, too!). And make time to talk to other teachers—whether you meet up in your school, at a conference, on social media, or on a message board—to think together about how to modify, adapt, and expand your instruction.

All Five Skills in Action: A Case Story

What does it look like when a teacher uses all five of these key thinking skills? This brief vignette from Engaging Young Engineers shows all these skills in action in an early childhood classroom.

Mariela, a preschool teacher, notices that 3-year-old Cassie consistently avoids drawing and writing. Mariela becomes curious—she wonders why Cassie avoids these activities, when all the other children in the class seem to enjoy them. They “sign” their names on the whiteboard when they arrive in the morning and sit at the writing center table drawing pictures during activity times.

Mariela is concerned that Cassie’s resistance to drawing will interfere with her development of important school readiness skills. The teacher displays persistence: she tries multiple strategies to engage Cassie in drawing activities. Despite these repeated attempts, Cassie still refuses to participate in any drawing or writing activities, and when pushed, Cassie becomes upset. Still, Mariela refuses to give up, and she believes Cassie can succeed. She thinks flexibly and decides to take a different approach to the issue.

Mariela decides to take observational notes on Cassie. Afterward, she reviews the notes and reflects on the situation. She thinks about what Cassie chooses to do most often and how Cassie has responded in the past when encouraged to use drawing materials. She decides to share her concerns at a collaborative meeting with the other teachers in the program. One of the teachers suggests they ask Cassie’s family about her drawing experiences at home, and they all agree this will be helpful information. The teachers also agree that they will all take observational notes about Cassie so they can build on Mariela’s observations.

At next week’s meeting, the teachers share their notes. Cassie’s parents reported that she did not seem to have an interest in drawing at home. The teachers were fascinated to learn, however, that Cassie did in fact engage in a writing activity that week. Cassie spent most of her time playing dress-up in the dramatic play area, but when another child brought a pad of paper and markers to the area to make a shopping list that week, Cassie started writing a list of her own.

The teachers in Cassie’s classroom display flexibility: they follow Cassie’s lead and come up with a new approach to try. They agree that Cassie might be more motivated to write when she is with peers in the context of an activity that is meaningful to her. The teachers come up with a list of new strategies for engaging Cassie in drawing and writing, all building on Cassie’s demonstrated interest in writing within the context of dramatic play.

****

When you hone your curiosity, persistence, flexibility, and ability to collaborate and reflect, you become an even better teacher. And when you explicitly model these thinking skills for your students, you help them become better learners. Which thinking skill do you want to focus on expanding this year—and teaching to your students?

SHARE THE INFOGRAPHIC

CHECK OUT THE BOOK

Engaging Young Engineers

Engaging Young Engineers

Teaching Problem-Solving Skills Through STEM

By Angela Stone-MacDonald, Ph.D., Kristen B. Wendell, Ph.D., Anne Douglass, Ph.D., and Mary Lu Love, M.S.

In this timely and practical book, you’ll discover how to support the problem-solving skills of all young children by teaching them basic practices of engineering and five types of critical thinking skills. Using a clear instructional framework and fun activities, you’ll help children birth to 5 explore big ideas and develop new ways of thinking through engaging and challenging learning experiences.

EXPLORE IT NOW

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post a Comment