13 Things Every New Inclusive Educator Should Remember

August 3, 2021

If you’re a brand-new teacher, and this fall will mark your first foray into the world of inclusive education, you might be feeling some trepidation as you prepare for your new role. A teaching job is complex and challenging even in ordinary times—but in the wake of a pandemic that turned life upside down and changed the rhythms of education for more than a year, teachers will have new issues to address, from student trauma to the effects of unequal access to resources during remote learning.

But no matter what extra challenges teachers may face this fall, there are some overarching, big-picture principles that every inclusive educator should keep in mind as they navigate the school year. Today’s post outlines 13 of these fundamentals, adapted from six popular Brookes books on inclusion. If you’re getting ready to teach in an inclusive classroom for the first time (or if you’re a seasoned educator looking for a few good reminders), these guidelines will help you support the academic and social success of every student and partner effectively with parents and other teachers.

Don’t prejudge a student’s competence. At the beginning of the school year, avoid making predictions or assumptions about a student based solely on the way that student looks, moves, or communicates. Always make the least dangerous assumption—that is, presume competence—even if you feel uncertain about a student’s abilities at first.

Dismantle your “deficit lens.” Historically, people with disabilities have often been viewed through a lens of perceived deficit—a vantage point that devalues the strengths, gifts, interests, and needs that all people have. Actively challenge this ableist viewpoint by dismantling the deficit lens and focusing on the positive qualities and support needs of each learner. Flip the language that’s often used to describe students—for example, instead of thinking of John as a “nonreader” who “can’t follow directions,” you might say “John enjoys listening to stories read by others and needs systematic reading instruction. He’s an independent thinker who will need some support to follow directions that are essential for daily life.” (See this blog post for a chart of quick tips on reframing “weaknesses” as strengths and needs.)

Establish collaborative communication with parents. Strong home-school connections are an essential part of supporting the success of students with disabilities (and all learners in your classroom). Early in the school year, talk to parents and find out how they’d like to communicate and how often they’d like to hear from your team. Some parents will appreciate phone contact; others may prefer the convenience of email or text updates. Welcome parents as partners in their child’s education, recognize the unique insights they can bring to the table, and invite them to participate in creating solutions to their child’s challenges. (Read this post on connecting and communicating with families for more tips.)

Acknowledge and respect cultural differences. Keep in mind that families from cultural backgrounds different from yours might hold different views of values you may hold in high esteem, such as independence and individuality. As an inclusive educator, it’s up to you to explore your own cultural values and beliefs, carefully consider how those beliefs might affect your interactions with students and families, and avoid “right versus wrong” assumptions about parenting styles and practices. You may have to adjust your assumptions and goals based on the family’s priorities. Inclusive and special education experts Maya Kalyanpur & Beth Harry suggest that educators “engage in explicit discussions with families regarding differences in cultural values and practices, bringing to the interactions an openness of mind, the ability to be reflective in their practice, and the ability to listen to the other perspective. Furthermore, they must respect the new body of knowledge that emerges from these discussions and make allowances for differences in perspective when responding to the family’s needs.” (Read more in the book Cultural Reciprocity in Special Education.)

Look beyond life skills. Educators and parents may sometimes prioritize teaching functional life skills to students with disabilities, underestimating  the value of academics. While life skills are important for everyone to learn, students with disabilities deserve the chance to acquire knowledge and a passion for lifelong learning. Academics help students establish interests that can lead to friendships and social connections. And academic learning can help all students develop critical job skills and inspiration for future careers—for example, learning about and enjoying scientific experimentation may eventually lead your student to apply for a job at a science museum.

the value of academics. While life skills are important for everyone to learn, students with disabilities deserve the chance to acquire knowledge and a passion for lifelong learning. Academics help students establish interests that can lead to friendships and social connections. And academic learning can help all students develop critical job skills and inspiration for future careers—for example, learning about and enjoying scientific experimentation may eventually lead your student to apply for a job at a science museum.

Embrace activity-based learning. Passive, large-group lessons don’t just pose learning challenges for students with disabilities; they don’t really engage and motivate other students, either. Embracing more active, creative, hands-on approaches to learning may take a little more prep work, but this strategy will pay off for all your students. Activity-based learning can include a wide range of options: individual or cooperative projects, dramatic or musical performances, multimedia presentations, educational games, and much more. Don’t be afraid to include your students in planning and designing the activities—it’s a great way to individualize their learning experiences, make use of their creativity, use their passions as teaching tools, and get them excited about participating.

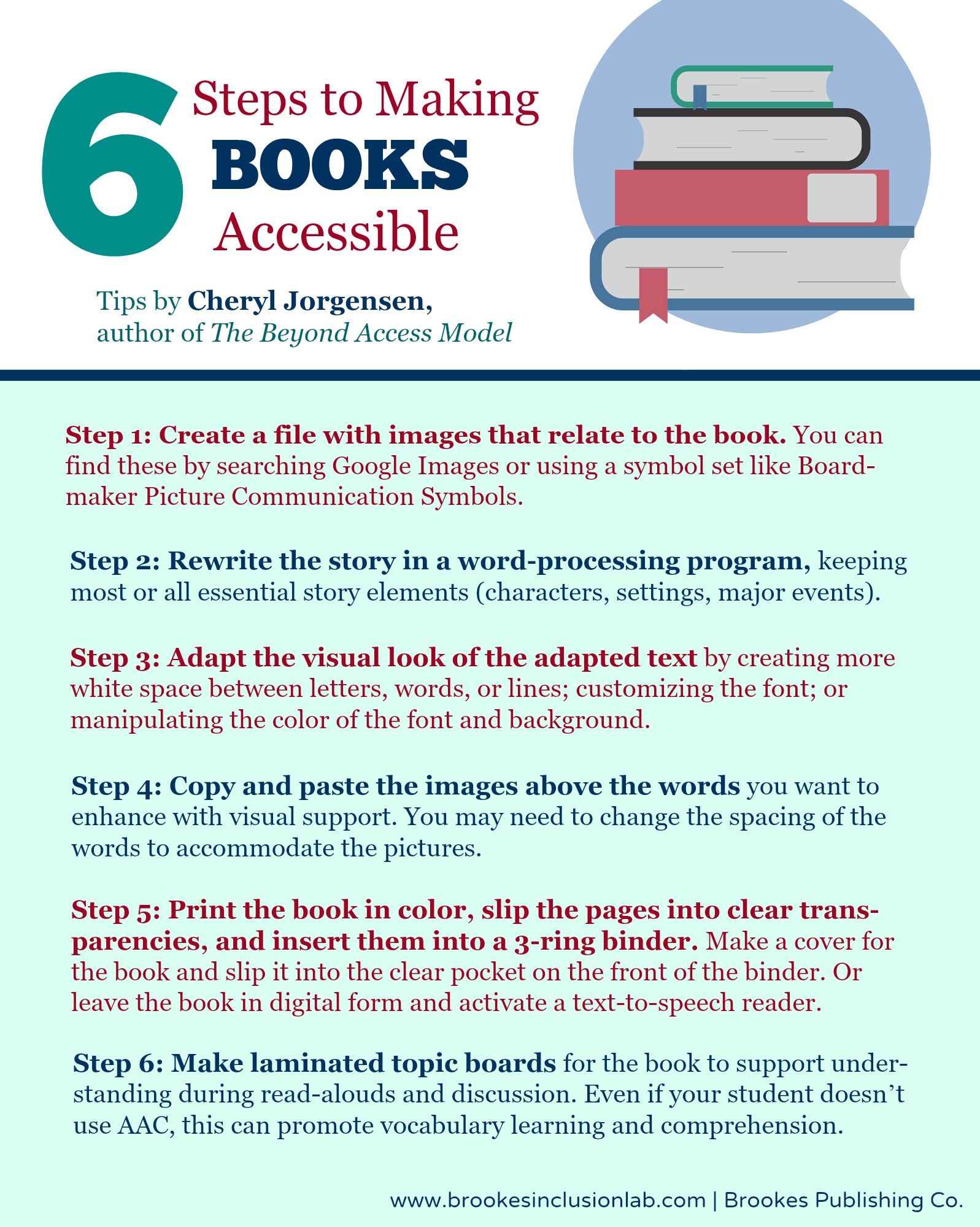

Make all things age-appropriate. To facilitate belonging, academic progress, and social relationships, students with disabilities should be treated like other students their age. Talk to your student about age-appropriate topics and events, in the same tone of voice you would use with their classmates, and encourage peers to do the same. Support your student in accessing age-appropriate clothing and school materials (you might want to tell parents about the need to supply their child with clothes and other items that reflect their age). Give your student age-appropriate learning materials—for example, instead of giving a Dr. Seuss book to a tenth-grade student with emergent literacy skills, look for accessible texts written at the student’s reading level that match tenth-grade literacy and informational content. (You can create your own accessible texts, too—the graphic below takes you through the key steps. Cheryl Jorgensen’s It’s More Than “Just Being In” has more in-depth guidance.)

Challenge biases when interpreting behavior. Be careful not to interpret your student’s behavior through your own preconceived notions about individuals with a particular disability. For example, if you notice that a student on the autism spectrum who uses AAC to communicate has been enjoying flipping through books, don’t assume she’s just stimming or getting sensory stimulation from the moving air. Take what expert Cheryl Jorgensen refers to as the “constructing competence view”: assume she may be communicating an interest in reading, and ask the SLP to add a “want to read” request on your student’s AAC device.

Remember you are EVERY student’s teacher. When you have a special educator or a paraprofessional in your classroom providing support to one or more students with disabilities, it can be tempting to think of them as the “real” teachers of those students, and see yourself as a sort of “host.” This is one of the most important misconceptions to dismantle. You are the teacher of every learner in your classroom. Assume ownership and responsibility for the learning of all students, regardless of disability and despite the presence of other professionals supporting their education. This mindset will benefit every student in your class—as Quick-Guides to Inclusion co-editor Michael Giangreco says: “Teachers who have embraced the challenge of teaching their students with disabilities often report that they have learned approaches that benefit their entire class and that they keep using after the student with a disability has moved on to the next grade.”

Ask yourself, “Am I setting the stage for future success?” Too often, students who score well on tests and other measures of academic progress still run into roadblocks to well-being—from unemployment to lack of social connections—when they enter adulthood. While collecting data about academic performance is important, it’s also critical to evaluate whether your students’ education is setting them up for a successful, self-determined future. As Michael Giangreco says in Quick-Guides  to Inclusion, “we need to continually evaluate whether a student’s achievement is being applied to real life, as evidenced by outcomes such as physical and emotional health; positive social relationships; and the ability to communicate, self-advocate, make informed choices, demonstrate personal growth, and increasingly access places and activities that are personally meaningful.” As a starting point, read these blog posts on self-determination, transition planning, and college prep and employment prep for students with disabilities. Also, check out the helpful and practical guidebooks in the Transition and Employment section of the Brookes Publishing online store.)

to Inclusion, “we need to continually evaluate whether a student’s achievement is being applied to real life, as evidenced by outcomes such as physical and emotional health; positive social relationships; and the ability to communicate, self-advocate, make informed choices, demonstrate personal growth, and increasingly access places and activities that are personally meaningful.” As a starting point, read these blog posts on self-determination, transition planning, and college prep and employment prep for students with disabilities. Also, check out the helpful and practical guidebooks in the Transition and Employment section of the Brookes Publishing online store.)

Always make time for team collaboration. Successful inclusive education is a team effort. As inclusion experts Julie Causton and Chelsea Tracy-Bronson say in The Educator’s Handbook for Inclusive School Practices: “In an inclusive classroom, the professionals are like tiles of a mosaic. Each person is an important contributor to the larger picture.” With busy schedules keeping everyone on the go, you might have to get a little creative to keep the lines of communication flowing between you and your fellow team members. Reserve 15 minutes before or after school to collaborate with the team, start a group text chat or stay connected via email, or go low-tech with a special communication notebook that the team can pass around and write in. (This blog post gives you more ideas for making time for team collaboration.)

Keep collecting and connecting. An inclusive educator’s education is never finished. Nicole Eredics, author of Inclusion in Action, stresses the importance of keeping a log of inclusion information and strategies and reaching out to other teachers across the country who are interested in talking about effective inclusive practices. “Bookmark websites, search Pinterest boards, keep notes, and take photos of materials and/or environments that are inclusive,” Eredics says in her book. “Share resources with [other teachers], such as inclusive lesson plans, classroom management tips, and helpful apps. Creating a network of support will help you feel confident as you develop your skills as an inclusive educator.”

Make “all children can learn” your mantra. Use this foundational belief as your guiding light, and it will inform everything you do. Whitney Rapp & Katrina Arndt say it best in their book Teaching Everyone: “What we believe affects what happens in schools in several significant ways. If we believe that some—not all—children can learn, we ignore children we think cannot learn. If we think some children can learn but others have to prove that they are capable of learning, we set up barriers to education for some children. If we believe that some, not all, children can learn, then that is what will happen.”

Finally, remember that you’re not alone—there are so many great sources of information for inclusive educators out there. In addition to the Inclusion Lab, we especially recommend the blogs Think Inclusive, The Inclusive Class, Inclusion from Square One, Ollibean, and Removing the Stumbling Block. And if you’re looking for some professional development books you can keep by your side to help you solve challenges, explore the Inclusive Education resources from Brookes Publishing.

GET THE BOOKS

The tips in this article were adapted from the following Brookes books on inclusive education:

Tips 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 from It’s More Than “Just Being In” by Cheryl M. Jorgensen, Ph.D.

Tips 3, 6, 9, and 10 from Quick-Guides to Inclusion, edited by Michael F. Giangreco, Ph.D., & Mary Beth Doyle, Ph.D.

Tip 4 from Cultural Reciprocity in Special Education by Maya Kalyanpur, Ph.D., & Beth Harry, Ph.D.

Tip 11 from The Educator’s Handbook for Inclusive School Practices by Julie Causton, Ph.D., & Chelsea P. Tracy-Bronson, M.A.

Tip 12 from Inclusion in Action by Nicole Eredics, B.Ed.

Tip 13 from Teaching Everyone by Whitney H. Rapp, Ph.D., & Katrina L. Arndt, Ph.D.

Write a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Post a Comment